Two years ago I joined a friend for one of the most extraordinary experiences in theatre I have ever had. We arrived to The McKittrick Hotel an hour prior to the announced time, and there had already been a noticeably long line. Sleep No More was rumored to be “an experience like no other”, but I admit that I was sceptic this would be a significantly different experience. Taking into consideration this was theatre at the end of the day, I wasn’t able to imagine anything beyond the familiar structure of audience vs actors. I was in for a big surprise.

All visitors (subsequently the audience) are required to wear (and keep on) a Venetian carnival-style mask throughout the entire experience. You are asked not to speak upon entrance, however, you are encouraged to poke around in corners and trunks and bookcases. Though you are asked not to touch the performers, they may approach and interact with you. These encounters can be as minor as a call for quick favor, or may also result in vanishing with you through a secret door that leads to a secluded room and a one-on-one experience with a character. At the end, you will have to figure your way out back to the rest of the crowd.

Although the general narrative stays the same, it is known that no two of these theatrical experiences are identical. The evolving of the plot is very fluid and based a lot on the audience’s reaction.

Sleep No More is a perfect example for exploring the boundaries of interaction. In The Art of Interactive Design, Chris Crawford describes a system representing interaction:

Input → Process → Output

The thing I find to be key in this system is the fact that “process” allows for unexpected transformation and interpretation of the information previously received. This as a result, may lead to a number of possible reactions. It may be safe to say that this kind of unexpected translation or transformation is more common in human to human interaction, and less in human to computer interaction, where essentially, the machine is programmed to react accordingly, making it the process and output limited.

In The Design of Everyday Things, Donald A Norman highlights scenarios where design has failed to communicate the way an object should be used. These mistakes in design, which happen more often than we may think, are likely to be a result of the designer thinking of the end user more as a machine and less as a user. It is crucial for design to be revisited and questioned multiple times, as well as testing and close observations prior to releasing the actual design. Norman also addresses a system similar to the one described earlier, only more specific:

Designer → System → User

When designing anything for the use of others, one of the most important things to keep in mind should be feedback. Allow your user to know if they are on the right track when engaging with your design. Is everything OK? Should something in the use of the device be changed? We are often challenged by poor design, leaving us as the end users in a vague scenario, having to guess ways of operation. Norman is not shy to put this responsibility solely on the designer. He points out 4 principles that should be considered by every designer before the release of an item or technology:

- Visibility : the user can see the areas for action

- Conceptual model : the operations are clear to the user

- Mappings : the relationship between action and result, cause and effect, is clear

- Feedback : the user receives constant feedback on the results of his/her actions

Keeping these principles in mind, I believe more thoughtful forms can be modeled, leading to less misuse and confusion. After all, interaction is a dynamic form of communication, and if the other side is not comprehending, you are the one to be questioned first.

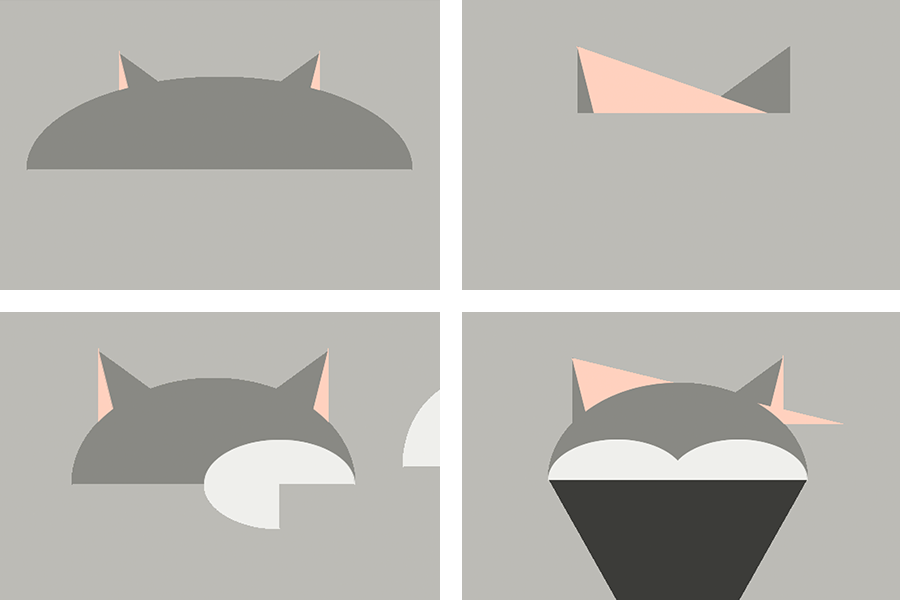

The image above was taken from Katerina Kamprani’s project: The Uncomfortable.